During...

After!

The Fresco of the Transfiguration in the Catholic Chapel is now complete. The internationally-acclaimed artist and iconographer, Aidan Hart, together with his team of Fran Whiteside and Martin Earle, completed the sacred image. There is timelapse footage of the whole project, two and a half weeks work in two minutes! Already the project - which is a significant contribution to the Christian patrimony of North-West England - is being recognized and has been reported in international journals.

After all the drama of the project's development, now is a good opportunity to reflect once again upon the story of the Transfiguration, why the subject was chosen for the University setting, and what the image says to us today...

“Jesus took with him Peter, James and John the brother of James, and led them up a high mountain by themselves. There he was transfigured before them. His face shone like the sun, and his clothes became as white as the light. Just then there appeared before them Moses and Elijah, talking with Jesus. Peter said to Jesus, “Lord, it is good for us to be here. If you wish, I will put up three shelters—one for you, one for Moses and one for Elijah.” While he was still speaking, a bright cloud covered them, and a voice from the cloud said, “This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased. Listen to him!” When the disciples heard this, they fell facedown to the ground, terrified. But Jesus came and touched them. “Get up,” he said. “Don’t be afraid.” When they looked up, they saw no one except Jesus”. Matthew 17:1-8.

The experience of Christ’s Transfiguration on the mountain is one of the most mysterious events recounted in the Gospel, revealing to us the fullness of who Christ is. To outsiders Christ must have been considered just another baby born in Bethlehem, another boy growing up in Nazareth, another carpenter working in Galilee. There was nothing to catch the eye, nothing to dazzle. But conceived by the power of the Holy Spirit within the womb of Mary, the Scriptures speak of how Christ, though in the form of God did not cling to his divinity but humbled himself and took on our human flesh. Whilst on earth, perhaps the greatest miracle of all, was that Christ’s glory remained veiled. But in this moment of the Transfiguration, the disciples – Peter, James and John – behold the glory of Christ. They are to understand that the man who stood before them was truly also the Son of God.

It is important to remember that this event took place within the context of prayer, and it is in prayer that Christ’s true identity is revealed to us. The Transfiguration is most apt for a university setting:

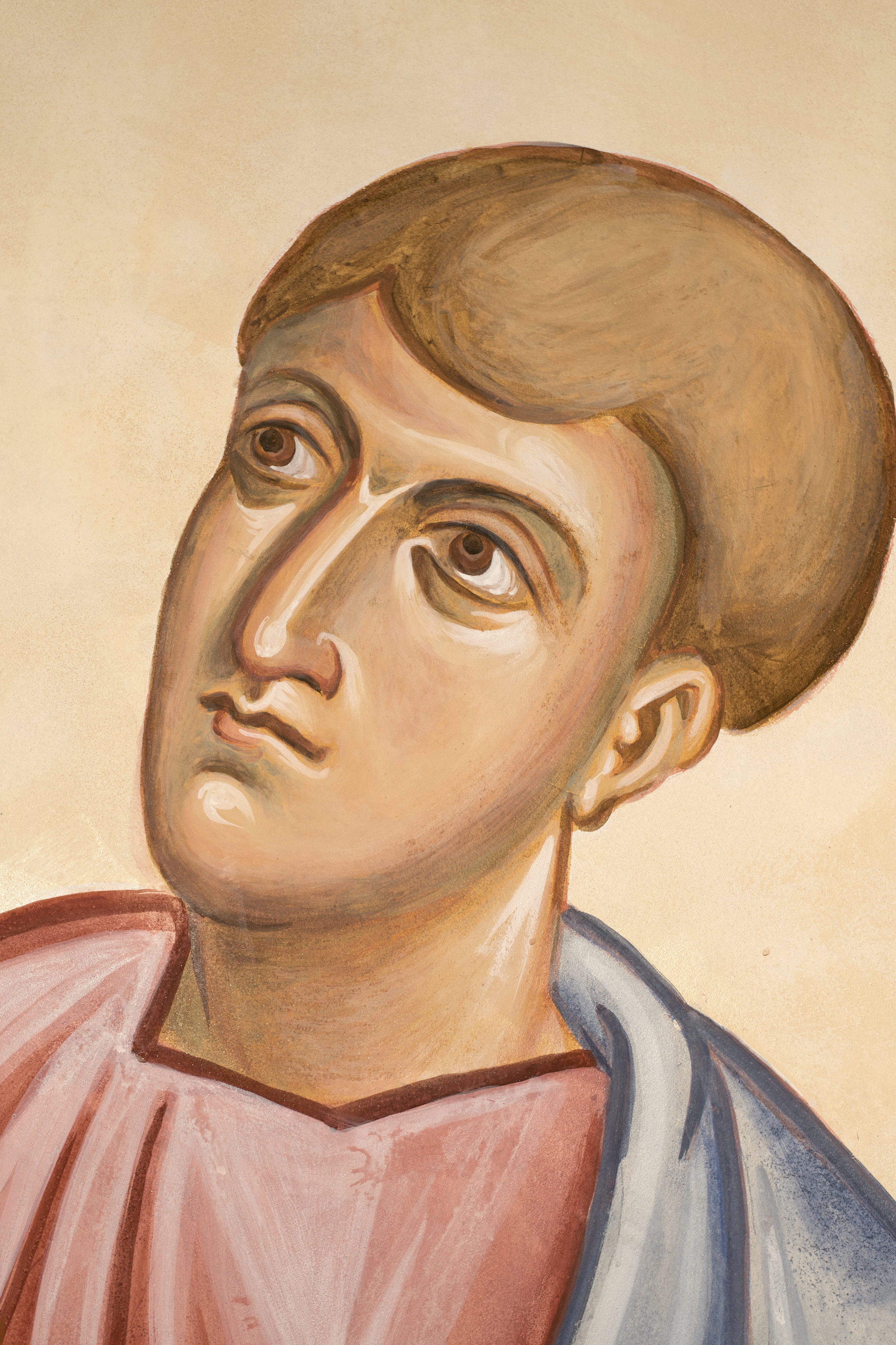

· First of all, there is the sense that Christ as the Teacher is revealing the truth to his Disciples, now as then (discipuli in Latin means students). One of the disciples, John, is without a beard for he was traditionally the youngest of the apostles, perhaps little more than 16 or 17 years of age, reminding us that the Lord calls us to His side from our youth.

The youthful apostle, John.

· The mountain too is an ancient image of ascent, the movement up and outwards from oneself, the leaving behind of what is familiar and the discovery of new views. In Christ, there is no contradiction between faith and reason, between the created world and the uncreated world, for in Him – the Logos – all creation has its being. All education should lead us out of the shadows of ourselves into the light of Reason.

· The Transfiguration says everything about who Christ is. As all the figures in the image look upon Jesus, Jesus looks upon us, inviting us to draw near to him, and discovering the truth of our identity in Him. Only in beholding Him will we ever discover who we are and what we are made for, that we too are called to be clothed in light, and we too are God’s beloved children, His sons and daughters, in whom He is well pleased.

· Finally, the role of art. ‘Beauty’, writes Pope Benedict XVI, ‘whether that of the natural universe or that expressed in art, precisely because it opens up and broadens the horizons of human awareness, pointing us beyond ourselves, bringing us face to face with the abyss of Infinity, can become a path towards the transcendent, towards the ultimate Mystery, towards God’.

Aidan Hart presenting the progress to a visiting group of icon writers from the NW of England.

Who’s Who?

Christ, in the early stages of his Transfiguration! The first coats of paint applied.

Christ – radiant in light, raising his hand in a sign of blessing. Notice the gesture of his hand of blessing: the two fingers together represent his divine and human nature whilst the three fingers together point to the unity of the Godhead, Father, Son and Holy Spirit. In his other hand, Jesus holds the scroll of judgement, which, for the time being remains rolled up, affording us time to respond to his call. The mandorla (which represents the radiance of the luminous cloud, signifying the majesty and glory of Christ) is blue, a colour which in iconography denotes divinity. Christ is light from light, true God from true God. The eight-pointed rays remind us of the days of creation: the seven days of creation are followed by the eighth, the day of the new creation, the eternal day which is breaking upon us. In this regard, what is fascinating about the Transfiguration is that not only is Christ shining, but his flowing garments shine too. So much more than a merely spiritual event, matter itself is being caught up in the mystery of God and through Christ the whole of the cosmos is being renewed.

The tablets of stone on which the Law was written, held by Moses.

Moses & Elijah. On either side of Christ, there stand the two great figures of the Old Testament: Moses holds in his hands the tablets of stone on which were written the Law, and Elijah, dressed in camel skins, holds a scroll, for he represents the prophets who proclaimed the Word of God. Whilst these two figures are speaking face to face with Christ who is the fulfilment of the Law and the Prophets, the other disciples are unable to behold Christ’s glory. Perhaps we catch a glimpse here of Heaven where we will all be able to see God face to face.

Peter, staring intently at the mystery before him.

The Apostles – Peter, James and John – are on their knees in adoration, screening their faces, and falling backwards before the glory of God. John has even lost his shoe, perhaps in the drama of the moment, perhaps too reminding us of Moses’s encounter with the Lord in the burning bush when he was asked to remove his sandals for he stood on holy ground. All three disciples are in part clothed in blue garments, sharing the life of Christ. The positioning of the disciples beneath Christ and the shape of the curved wall extending out towards us helps us to understand that we too are participants in this event, embraced by the mystery of God’s light.

John, kneeling on the mountaintop, has lost his shoe in the drama of the moment.

The mountain with its solid, craggy top, emphasises that this divine event is taking place on earth. Its ruptured surface gives the impression that the earth is trembling beneath the majestic voice of the Father from on High. The tree to the side points to Christ’s forthcoming passion, about which Jesus, Moses and Elijah are speaking of, reminding us that a share in God’s glory can only come about through a sharing in His cross.

A curlew. Anyone who has roamed on the Moors around Lancashire will be familiar with its haunting call.

The foreground with its gentler hills displays plants and wildlife that are characteristic of the Trough of Bowland, an area of upland bog that flanks the city of Lancaster. There is a curlew with its down-curved bill and haunting call, and a hen harrier, a beautiful, agile bird of prey, renowned for its aerobatic sky dances. There is also Bog Rosemary, a heath shrub, and Cloudberries, a variant of the wild rose. These remind us that the event of the Transfiguration is not something that is limited to first-century Palestine, but an event that continues to become present in our own day as we bend our knee to Christ, who makes himself present in the celebration of Mass, renewing the whole of creation and the whole of history.

Bog Rosemary

The Project.

Lee Richards & Co, our wonderful lime plasterers, who spent two weeks over Christmas building up the layers of lime.

Fran, Martin and Aidan, enjoying a lunchbreak (very healthy looking one too!)

The spectacular icon of the Transfiguration was executed by the internationally-acclaimed artist and iconographer, Aidan Hart, in March 2017. Using a combination of water, egg and pigments made from natural earth and semi-precious minerals (such as azurite), the image before you was built up from basic outlines. Each figure was modelled with layer upon layer of tempera, and over the course of two weeks, it seemed as if the figures were released from the wall, and finally brought to life as they received a sheen of light over the rich colours from which they were made.

This process reflects the way in which God has made us, drawing us from the dust of the earth and breathing into us His Spirit. The transformation of lime, grit, pigment and water into the living image that can be beheld today is itself deeply sacramental, a transfiguration of matter itself.

Drawing from the rich and ancient iconographic tradition exhibited in the ancient monasteries and churches of the East – St Catherine’s Sinai, Constantinople and Thessalonika – the image of the Transfiguration in the Catholic Chapel at Lancaster University presents a significant addition to the Christian patrimony of the North of England. A profound debt of gratitude is owed to Bishop Michael Campbell, the staff, students and friends of the University of Lancaster, the Chaplaincy Centre Management Group, Aidan Hart, his apprentices and those who prepared the groundwork, and the countless benefactors, who have enabled this project to come to its fruition. The artist writes, ‘I pray that, like Christ’s transfigured garments, this inanimate paint might be a bearer of uncreated light to those who stand and pray before the icon’.

Students admiring the work on the night of its completion.

“You can admire a painting by your eyes, but you admire an icon by your soul. When you see this fresco and then go back home, all you can think about is the Transfiguration”

“What a transformation! What a transfiguration! Our’s is an incarnational religion, so the visual aspects of our churches should speak to our senses - this certainly does, raising the heart and mind to God.”

“I love the inclusion of the local fauna and flora which I see on my drive to work through the Forest of Bowland. Let it inspire us (and the many future cohorts of students and staff) to find Christ everyday in our work. Thank you too to the artists for saving us from climbing to the top of the mountain; each day we can come just here to see them!”

“I’m so grateful this happened during my extended visit to Lancaster University. Seeing this artwork grow each week has been a beautiful experience.”

“I am new to faith, but in a moment of darkness I came into this chapel and I locked eyes with Jesus and felt touched by His presence.”

“The fresco is beautiful and filled with a holy presence. Christ’s gaze seems to be an unequivocal invitation to follow Him, to enter into Him, into the eye of eternal life behind him, for He is ‘the Way, the Truth and the Life. Anyone who follows me will have the light of life’.”

“The Fresco is simply AMAZING! Now the chapel looks more alive, and immediately invites to prayer and reflection. Beautiful work.”